That is a huge question, and there is probably no currently comprehensive response

If we look at the transformation of the tyre recycling sector across most of Europe and much of North America, we can see that the situation has advanced from the days of large-scale landfills and tyre mountains. In all but a few cases, these large-scale dumps have been replaced by “recycling” operations.

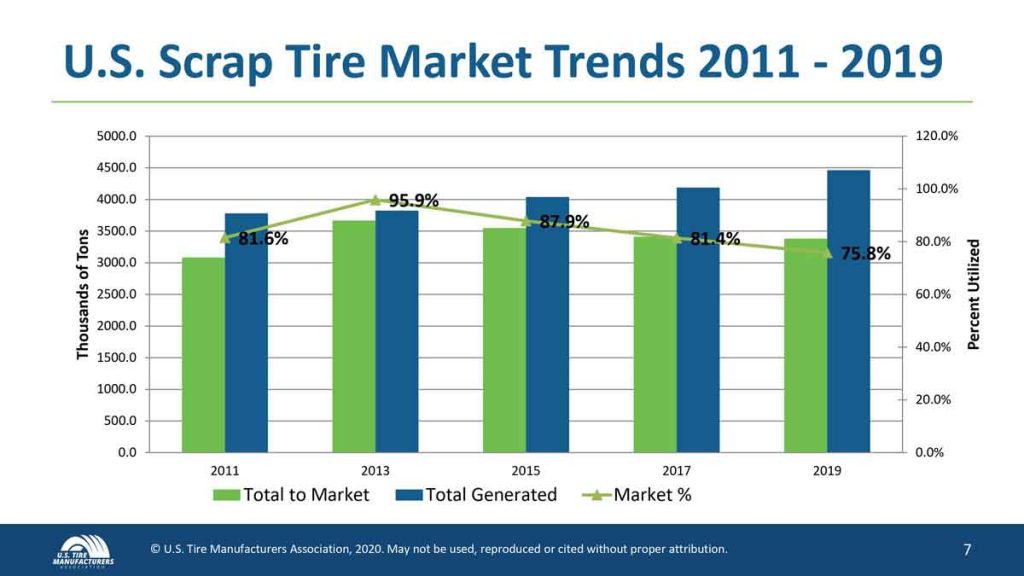

In the USA, tyre recycling is a state responsibility – in most states – that is to say, the state funds tyre recycling through a recycling fee, or not, as the case may be. According to USTMA, the recycling rate is around 71 per cent, but that figure still includes landfill. So, the actual “recycling rate” may well be much lower. One measure is that if the recycling rate in the most populous state in the USA is only 54 per cent, then the recycling rate in much less densely populated states with poorer infrastructure must be even lower.

Take the landfill out of the equation, and the USA is probably not performing even as well as the 71 per cent that the USTMA suggests. That is clearly not sustainable.

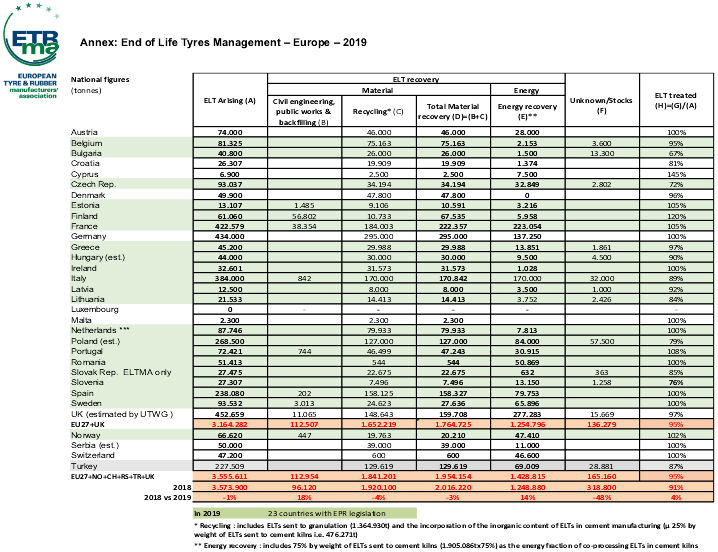

If we look at the European model, tyre collection levels are, for the most part, high, anywhere between 80 and 100 per cent, according to the European Tyre and Rubber Manufacturers Association (ETRMA). That is to say, the tyres collected on behalf of the members of the ETRMA are high.

Collection and recycling, though, are two very different things. It is possible to collect end-of-life tyres, which is the easy part of the equation. In the UK and Germany in particular, the free market allows the collection of tyres and the accumulation of tyres – to a point, without any recycling. In the past, this had led to large stockpiles of tyres, precisely as it did in every other European state before EPR was introduced. That is not to say that EPR can solve everything.

Over the years, Tyre and Rubber Recycling has seen many claims of 100% recycling. A Spanish government spokesman told a conference that Spain only exported three per cent of its tyres. Yet, one company alone was responsible for shipping what amounted to around five per cent of Spanish tyre arisings.

Aliapur claimed to recycle 100 per cent of its members’ EPR arisings, but that figure included exports to 13 plants outside France, some in the EU, and some in North or West Africa. Aliapur still has a media release on its site about sending shredded tyres to Senegal – a country that does not have the capacity to recycle its own tyres.

The UK ships somewhere over 200,000 tons of tyres to India alone, which is almost half of UK arisings. Peter Taylor at the Tyre Recovery Association tells us that the figure is now much less, closer to 100,000 tons going to India, with much of the balance going to other markets such as Turkey. However, Indian figures from Mumbai Fabrics show that the company imports around 40 per cent of the tyres coming from the UK, and their imports stand at 80,000 tons, which would suggest imports to India from the UK stand at 200,000 tons still. Further figures show exports to India at 19,600 tons in February 2022. If that is extrapolated to a full year, that figure becomes 235,200 tons per year going to India from the UK.

The UK is one of many European countries shipping tyres to India, Pakistan, or anywhere else that will take them legally or otherwise.

Our governments should be asking if this is truly sustainable. If it were not for otherwise empty containers heading back east to India and China, exporting ELT to just about any market would be unsustainable.

Then there are the current uses of tyres that are recycled in the domestic markets. By far, the largest sector remains sports surfaces – both crumb rubber infill and elastomer-bonded surfaces. On the energy recovery side, the cement industry could take many more tyres than they currently do, but environmental and stakeholder issues appear to limit how many plants can use tyres. I refrain from saying burn tyres, even though that is precisely what they do.

Is the use of crumb rubber infill sustainable in the longer term? There are only so many playing fields that can be converted to artificial turf. Eventually, those playing fields themselves will need recycling – IF the European Commission allows rubber infill to continue as a market.

Using tyres in cement kilns is a disposal route, and if it replaces fossil fuels, then it is more sustainable than not burning tyres in cement kilns. It is a similar case for cement as a waste to energy fuel. It is about the disposal, and replacement of fossil fuels. However, tyres contain oil and carbon black made from oil and burning those resources is not truly sustainable.

Much is made of using tyres for asphalt, and there are arguments for the use of rubber-modified bitumen, but there are arguments against its use, and some of them have little to do with rubber recycling. So, we will keep this discussion for another day.

There are two growing markets for tyre-derived materials. One is the resurgence of reclaim or devulcanised rubber. Reclaim is the popular and traditional name given to recycled rubber in India. Devuclanisation is the modern, cleaner version of the process. Either create a devulcanised rubber product that can be re-entered into the manufacturing process at some level. It is perhaps the most sustainable route to rubber recycling, taking materials from tyre to tyre and keeping a circular market, or at least as circular as it can be. But there is entropy in the performance of devulcanised rubber, and it can never fully replace natural rubber or SBR. It is more than a filler but less than a full-performance rubber.

The other growing market is indisputably through pyrolysis (by whatever name). Here the purest aim is material recovery, and for the most part, that is steel, process gasses, recovered carbon black (once properly processed), and tyre derived oil.

The reality is the production of a carbonaceous char, which needs refining and processing; usually, process gases, and the oil needs filtering and processing, even if it is drawn off in different levels in a condensing process.

The oil cannot, generally, be used as a fuel on the market without further treatment and approvals. However, it can be used as a basis for the pharmaceuticals sector or as a base for further refining to create fuel oils – even for aviation.

Pyrolysis operators talk of “no emissions” but the reality is that they will, if they use their gas/ oil to generate electricity, create Carbon Dioxide. For some lobbyists against pyrolysis, that is a huge argument on their side. – QV the objections to the Osnabrück plant.

Now, we all talk about sustainability, and we speak as if there is some Promised Land where there will be Zero Waste, but the reality is that we are kidding ourselves. There will always be waste in recycling, and there will always be an entropy in quality or performance. Additional costs will always be included in recycling that are not required when using virgin products. There will always be that element that we cannot recycle.

This brings me back to the USTMA and the ETRMA. Here, we have two large organisations representing some of the largest companies in the world and trying to sell the idea that they are sustainable through manufacturing and recycling.

However, there needs to be more transparency, exports are listed as recycling – not all exports get recycled responsibly, and landfill, in some cases, is still called recycling. Few, if any, in the industry are willing or able to say, we can go thus far and no further. The tyre industry is not alone in this, and it can also be found in other sectors.

When we discuss sustainability, government and industry start playing a huge game of smoke and mirrors. As things stand, the only government that has taken a position has been Australia and there, the country is using legislation and funding to drive its waste sector to become more circular, more sustainable, and more responsible -We need our environmental departments to get real, to take on the challenge of dealing with waste in our domestic markets. To stop avoiding the difficult questions and make things happen.